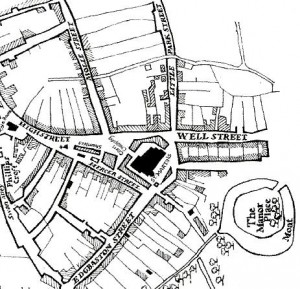

Depiction of medieval Birmingham at the end of the 13th century with St Martin’s Church sitting at the centre of the town.

A recent talk I gave for the University of Birmingham’s People, Places and Things series of seminars prompted me to write this latest instalment about medieval Birmingham. In fact, it was a question from a member of the audience after I presented the video of Exploring Medieval Birmingham, 1300 (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JZq9cBzrIVI) that determined the topic of this blog. The person in question asked if I’d thought about superimposing images or footage of Birmingham’s present-day streets over the medieval depictions illustrated in the video. Nice idea, and yes, I did think of doing exactly that, but budgetary and time constraints prevented me from doing so, but that isn’t to say that this can’t be achieved in the near future. Nevertheless, until then this blog will attempt to fill a ‘void’ in going half way to doing just that.

This map illustrates the early town that Peter founded. Notice the original triangular shape with four of Birmingham’s earliest roads branching from it: High Street, Edgbaston Street, Molle Street, soon to become Moor Street and Park Street, also at one stage called Little Park Street. (Source: Birmingham: The Building of a City by Joseph McKenna, pg 17).

The many different types of street name can reveal an abundance of information relating to topography or geographical location, natural features, types of industries or even people. It seems that the streets that shaped the medieval town of 1296 were largely ‘signposts’ of locational names or topographical features. One example is Super Montem, translating as ‘Upon the Hill’ and this isn’t hard to appreciate when you realise that this part of town really did and does sit at a higher level than the land leading downhill towards St Martin’s and Digbeth, suitably reflected by its current name, High Street. Then there are the convenient indicators of important trading routes such as Edgbaston Street, named after the Anglo-Saxon manor of Edgbaston, meaning Ecgbeald’s Farm. As Edgbaston was seemingly at one time more successful than Birmingham, as indicated by its higher valuation in Domesday Book, it’s perhaps natural that a road should lead to such a neighbouring settlement. After all, it’s very likely that Birmingham’s inhabitants were trading with Edgbaston’s and vice versa and not to forget that Edgbaston Street led to even more important locations like Northfield. Valued at £5 in Domesday, Northfield was one of the more prosperous manors in the wider area, worth five times as much as that of Birmingham. Moreover it was also once owned by the same overlord as Birmingham: William Fitz-Ansculf whose power was centred on Dudley Castle. So perhaps the street also marked the importance of a wider trading route, as well as leading to Edgbaston itself.

Novus Vicus or New Street is an indicator of Birmingham’s growth and prosperity as new roads were being built presumably to accommodate more inhabitants and trading ventures. Perhaps also, the adjective ‘new’ reflects the age of some of the other streets in the town as they had presumably been in existence for some time to warrant the latest road being called new.

Judging by the question that prompted this blog, people naturally want to know what Birmingham’s oldest streets look like today. It comes as no surprise either that most reside in what is the oldest part of town; the original planned settlement Peter de Birmingham carved out in 1166.

This is still one of the busiest parts of Birmingham today bustling with shoppers and inhabitants, now paying their ‘tolls’ and ‘rents’ to a different ‘lord of the manor’. On account of the scale and size we had to adopt for the model of medieval Birmingham, the likes of New Street isn’t featured, so I’ve simply focussed on the streets that are depicted to illustrate what these medieval route ways look like today.

This brings me on to Edgbaston Street, which in the 13th century was home to surely the smelliest industry in town: leather tanning and judging by the archaeological excavations in the area this trade made the greatest mark upon the industrial endeavours of medieval Birmingham. As an essential material in the Middle Ages, leather goods were a staple of everyday life, as were other goods made from horn and bone, which inevitably grew out of the presence of the tanning trade. Today, Edgbaston Street has exchanged tanning for trading of a different sort, but you can still nevertheless find leather goods, minus the noxious smell, that is.

Park Street or le Parkestrete was developed to make way for the many burgeoning industries, thereby cutting into the lord’s deer park, on what was then the edge of town. Although Park Street no longer lines the periphery of Birmingham, it does in many ways mark the edge of its shopping quarter lying adjacent to Selfridges and its attached car park. In this sense, Park Street is still on the fringe of Birmingham for many, particularly the enthusiastic shopper who merely walks this medieval road in pursuit of one of Birmingham’s biggest twenty-first century industries.

Much like Park Street, Overparkstret was also testament to the growth of Birmingham, with the lord once again sacrificing more of his own land for the good of the town, and of course his own pocket. The name is simple and reflects exactly where this new road would lie: ‘over the lord’s park’, or at least part of it. Maybe Overparkstret and Le Parkstret were cut at the same time, maybe they weren’t, but what is clear is that they came into existence to facilitate the expansion of some of Birmingham’s early industries like tanning and pottery making.

© Birmingham Museums. The beginning of Park Street in the 13th-century town around where Selfridges is today.

Perhaps the word park in two of the town’s roads which also lay very close to one another was slightly confusing for its inhabitants and traders, as Overparkstret was eventually renamed. In 1344 we find the earliest known reference to its new name: le Mulestret or Moulestret, in honour of the richest family in town, after the De Birminghams, at least. As we know, le Moulestret is today’s very own Moor Street, becoming the second of Birmingham’s medieval streets to accommodate a train station. We arguably have Roger le Moul to thank for this name change, and it’s indeed ironic that his surname translates as the small when we know he was a man of great property. Owning most of the land in town after William de Birmingham, he certainly ensured that his name and his family’s legacy would forever be preserved in his hometown.

Junction of Park Street and Moor Street where we think Roger le Moul held just some of his numerous burgage plots in 1296.

Last but not least, we finish with Super Montem, now High Street, which is only just visible at the very edge of the scale model. True to its name it still sits on higher ground, which is why I always suggest that people make the effort to stand at the top of High Street and look downhill towards St Martin’s Church. Although the natural topography has been slightly distorted by the most recent Bull Ring developments, you can still get a ‘flavour’ of what the medieval landscape once looked like in terms of its gradient.

Almost identical to the previous image in terms of position, High Street today is still bustling with shoppers and in the distance St Martin’s steeple peers up towards the higher ground.

Street names are really an excellent starting point for beginning to understand the physical development and topography of places, and sometimes the most ordinary of names, just like Park Street, lying in the most unassuming parts of town, can with a bit of detective work, really reveal a ‘hidden’ or forgotten history of a place. These muted relics of the past can tell us much more than you’d ever imagine, acting as signposts to a displaced landscape or in some cases subtly pointing to a terrain still very much intact, but obscured by the urbanisation of the modern city. Nevertheless, if we take the time to look hard enough, we can develop these ‘negatives’ in to fully-fledged images and create a colourful depiction of these ‘lost’ landscapes.

An original version of this article (with even more images!) can be found here: http://sarahhayes.org and don’t forget to take a tour of medieval Birmingham here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JZq9cBzrIVI

Sarah Hayes

Follow me @HayesSarah17