From Cabinets to Coffins

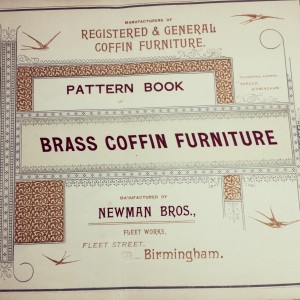

Possibly Newman Brothers’ first coffin-furniture catalogue, circa 1894. Familiar with brass since 1882, they continued to use this material in their new business venture producing coffin furniture from 1894 onwards. © Newman Brothers at The Coffin Works.

One of the most common questions people seem to have in relation to Newman Brothers is ‘why did a coffin-furniture manufactory choose the Jewellery Quarter to run their business from…wasn’t that an odd place?’ The short and simple answer to that is no, surprisingly not, but I understand why people initially may draw that conclusion. Newman Brothers were originally brass founders, established in 1882, operating from premises in Nova Scotia Street in what is the Eastside area of town today. As such their business was based on casting an assortment of metal articles, in this case, largely cabinet furniture from molten brass. But by 1894, just over ten years later, they had moved to new premises at 13-15 Fleet Street in the Jewellery Quarter. This move also spelled a slight change in their production line.

They were now listed as ‘Coffin Furniture Manufacturers’ and specialised in the production of general brass furniture. I say slight change as coffin furniture is, in fact, a natural extension of the jewellery and ‘toy’ trades and their many ancillary trades, using not only the same materials, but also incorporating the same skills and processes to produce various metal goods.

Casting ladle from the Newman Brothers’ collection, discovered in what was their tool room. This was probably used to pour the molten metal into cast-iron dies when Newman Brothers were brass founders and certainly during their years at Fleet Street as coffin-furniture manufacturers. © Newman Brothers at The Coffin Works.

Central to the production of both trades was and is (especially in terms of today’s jewellery production) the drop stamp, which uses heavy metal weights known as dies and punches with chiselled designs, on a pulley system to ‘stamp’ out products. So, the materials, machinery and methods of production were identical in both the jewellery and coffin-furniture trades, with the main exception being that drop stamps for the latter were much bigger, incorporating more weight to produce the larger items. Whether you were making a badge, a breastplate or a brooch therefore, the manufacturing processes involved were the same. The only difference was the intended use of the finished article. In this respect it made perfect business sense for Newman Brothers to relocate to the Quarter, as this new locality positioned it amongst a hive of thriving skills central to the production of coffin furniture, as well as allowing them to continue their tradition of casting.

A Newman Brothers’ backplate and ‘swing’ handle from circa 1894-1900. Although a different shape, the familiar form can be seen in its resemblance to the cabinet design on the left of this image. © Newman Brothers at The Coffin Works.

A Newman Brothers’ registered design from 1884 depicting a cabinet backplate and handle. © The National Archives.

The company’s transition from cabinet to coffin furniture was equally a natural development rather than a radical innovation in their product line. Take the two images above for example. The one on the left shows an 1884 Newman Brothers’ patent design for a cabinet backplate and handle, and was one of their earlier registered designs as brass founders. The other is yet another backplate and handle, but this time, intended for a coffin rather than a cabinet. Although flora-inspired designs for coffin furniture were common during this period, fauna-based patterns rarely seem to enter the equation. In this respect, the form and function of what Newman Brothers were producing largely remained stable, but the aesthetics of their designs altered to suit the backdrop of their new business.

Brass founders were renowned for making a range of different products and because of the ease with which coffin furniture could be produced, many non-specialist firms could quite comfortably ‘tap’ into this line of business, which means that there’s a good chance that Newman Brothers were already making some goods for the funerary trade before they became specialist manufacturers. No doubt they also had an existing clientele to some degree too, making their transition into the funerary trade smoother, and it would seem that their move from cabinets to coffins was most likely financially motivated. The transient nature of the funeral was simply bigger business than the permanence of home furnishings.

Sarah Hayes, Collections and Exhibitions Manager at Newman Brothers at The Coffin Works.

Follow progress @HayesSarah17 and @CoffinWorks

We’ve always said some of the more secular designs would make great draw and cabinet handles.

Spot on, Simon! By 1895 the partnership between Alfred and Edwin was dissolved, which was even announced in the London Gazette. I think you’re right that there’s more to this story though. To them, it wasn’t a huge leap making coffin furniture and the Victorian obsession meant that money could be made. Although it’s speculation, it’s of an ‘educated’ sort and that’s what excites me the most: colouring this Newman Brothers’ picture!

This is really interesting stuff, Sarah. My guess is that as general brass founders Newman Brothers found themselves doing more and more coffin fittings and decided to take the plunge and specialise entirely in this area, taking advantage of the late Victorian obession with big funerals. If I remember rightly, one of the brothers then pulled out of the business pretty quickly, suggesting perhaps that there was disagreement over this move?